As published on sidetracked.com

Over 7 days and 17 hours, amateur canoeists Oliver Bailey and Mathew Bennett paddled 1,000 miles through the wilds of Canada’s Yukon Territory and Northern Alaska in the bi-annual Yukon 1000 event, the world’s longest and most extreme international canoe race. They finished 8th out of 14 teams. Oliver Bailey recounts fragments of their experience.

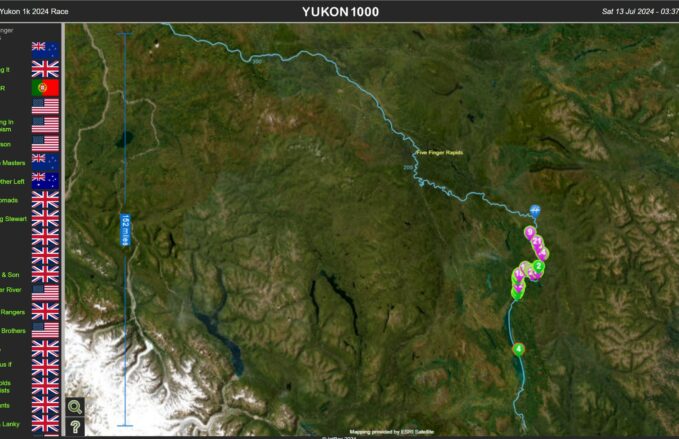

At the pre-race meet in Whitehorse YT the organisers warned us of sleep deprivation, dehydration, hypothermia, and potential savaging by grizzlies. They told us of these risks while emphasising that we were unsupported and there was little they could do in the event of an emergency. Satphones and tracking devices would be essential items for our survival.

Our training schedule in the months prior to the race had amounted to little more than paddling around a basin in London’s Docklands and a weekend in the Scottish Highlands on the Caledonian Canal. We’d chosen not to practise on the river during the pre-race camp, so had zero experience of fast-water canoeing.

After an administrative squabble on the start line, Matt and I watched the entire field disappear on the horizon before we’d climbed into the boat. In the first 200m on the water we learned that our race canoe was not designed for men of our stature and seemed keen to invert. Pitted against race veterans, competition paddlers, and disciplined amateurs, our inadequate preparation resulted in an entirely deserved position at the bottom of our type class.

Several hours later the river broadened into the glacially cold waters of Lake Laberge, an intimidating 50km-long behemoth. Ahead in bow position Matt shook his head. ‘We whinge across the Atlantic for fifty days and now we’re on a plank of wood… in the Arctic.’ We’d both been adamant after our trans-Atlantic row that we would never step into a boat together again, but hatchets had been buried, hugs had been administered and we were back in a boat and loathing it.

We found the canoe comedically snug, with a beam uncomfortably close to the waterline due to our combined weight of 230kg. Our poor understanding of stroke physics further compromised the hull’s dynamics. We were particularly effective at negating each other’s power by mistiming the catch, and in those early hours as we crawled along, tilting to the point of inversion after every stroke, it all felt a bit hopeless. By day two we were considering an early retirement at Dawson City, 300 miles north –the last settlement before the point of no return.

The Yukon River’s magnitude is difficult to define. It’s perhaps comparable with the Great Lakes of the US or the inland seas of Eurasia, a vast plain of water bellowing through the wilderness. At every bend it surprises, offering new configurations of river, terrain and flora. An enormous volume of water rushes over a relatively shallow bed, circumventing countless obstacles. Its vertical tree- and root-torn banks are scarred by winter ice ripping through the terrain, marking a clear delineation and enabling navigation whenever there is confusion of heading.

Beyond its banks lies a seemingly endless horizon of boreal forest and rocky peaks, occasionally dimmed by the charred remains of natural fires. The silence is interrupted only by the rush of water and the crack of eroding banks as trees collapse from above and begin their long journey towards the Bering Strait.

As the week wore on, we passed the midway point and began to adapt to race conditions. We had graduated to passable canoeist status and what we lacked in technique we made up for in raw power. Matt’s OCD served us well with his 50 frantic strokes and reward system; the reward was a micro-adjustment to his seating position and a few seconds of lumbar relief before the reset. Our talk of early retirement had faded from memory and we edged up the field, passing rival teams who looked as bemused at our progress as we were.

Our only capsize occurred on a failed landing attempt, our perceptions so blinded by fatigue we misjudged the boat’s angle of attack and struck a bank at 45˚, inverting instantly. As I rose hyperventilating from the shock I observed my only paddle drifting away at four knots. I crawled to the bank, sprinted 20m and dived back in to grab it while Matt anchored the boat and tried to recover other lost items.

Once into the wilds of Arctic Alaska, the topography shifted from boreal forest to a desolate tundra and maze of islands. After a rare period of heavy rain and wind, the afternoon sun returned and, exhausted, we took our first meaningful daytime break of the race. After sliding onto a sand bar and crashing down to rest, we shared a ration pack while conversing about life back home and our plans for the future. For 20 minutes, we compartmentalised the race and simply appreciated our surroundings and this island paradise, in the Arctic Circle, above the 66th parallel.

Our nightly camp and four-hour downtime period was punctuated by involuntary muscle spasms, bear panic, and clock-watching. We’d fall out of the tent at 4.15 am, heave on our mud-filled shoes and defrag the site while mosquitoes the size of houseflies swarmed. In those early hours neither of us would offer much in the way of conversation, either too focused on pain management or lost in reverie and a longing for our families.

With no more than 24 hours of rest over the week, our sleep deficit increased in severity during those final days. Pangs of paranoia would grip us. We experienced hallucinations of forms on the bank that simply were not there. We attempted to hack the deprivation and pain by concocting a witch’s brew that contained muddy chlorinated water, coffee, electrolytes, and soluble codeine.

The Dalton Highway Bridge – and race finish line – appeared like an apparition in the twilight, its form sharpening as we inched closer. ‘Four miles?’ Matt said with a wince. ‘Will anyone be there or are we hauling the canoe up ourselves?’ I asked.

To our relief the race organisers, John and Harry, were waving at us from a bank behind the bridge. We launched into the mud, staggered up the bank, and engaged in a much-needed four-man group hug. ‘You’re eighth,’ Jon said with a grin, pressing weighty finisher’s medals into our palms as we blinked at each other, neither of us truly comprehending our achievement.

Back home in civilisation, Matt and I continue to dream of the Yukon and its isolated communities living in that majestic riverscape, its inhabitants still perplexed by the sight of two Englishmen in their Y-fronts drifting past in the Arctic sunshine.

Oliver lives with his family in East London. He is planning to trek 1,400km up the Namib Desert in January 2020 with his regular NSPCC challenge partner and buddy Mathew Bennett.