Originally published on stuff.co.nz, by Mike White & Iain McGregor, January 6th 2023.

This is Part One of Finding Ben, the story of Ben Lott’s remarkable recovery from an accident that almost ended his life. You can read Part Two here.

The documentary above tells Ben’s full story.

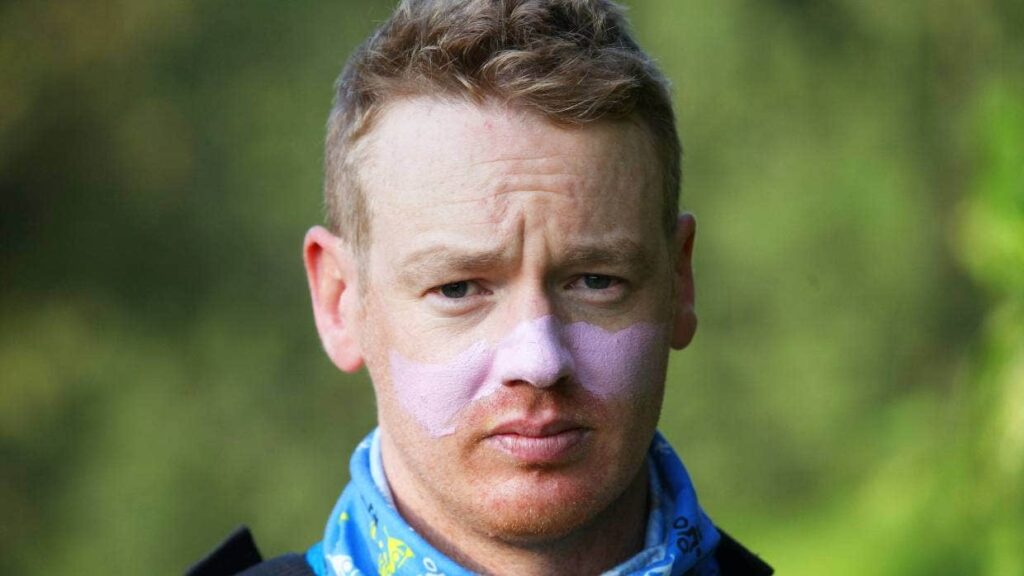

In March 2018, Ben Lott fell and suffered a severe brain injury while competing in an adventure race. Two days later, he was found disoriented in the middle of a forest by fellow racer Scott Worthington. Over the following days, Worthington helped Lott make it to the race finish. Over the next four years, he stayed beside Lott while he made an incredible recovery. This is the story of Finding Ben.

The accident was so simple.

Just a slip.

And then godawfulness.

Coming down wooden steps at the end of a gruelling haul during the GODZone adventure race, Ben Lott either fell asleep or just missed his footing.

Whichever it was, he ended up on his side, screaming.

After a while, he seemed okay, so carried on.

But two days later, another team found 27-year-old Ben sitting beside his bike in the middle of a forestry road, concussed and confused.

That team’s leader, Scott Worthington, decided the two teams should stick together for Ben’s safety.

And over the next two days, that’s what they did, till they crossed the finishing line in Te Anau.

Scott, then 61, who’d retired to Central Otago from Auckland after selling his business, had previously bumped into Ben during adventure races, but didn’t expect they’d have anything more to do with each other after GODZone.

Weeks later, however, he got a crank call, with someone gabbling incomprehensibly down the line.

But just before he hung up, Scott realised it wasn’t a hoax – it was Ben Lott, and he was trying to tell him something important.

“I just wish I had a second body, I could chuck the shit at for just a day… be able to taste and smell again, feel the right side of my face, all the confusion and memory loss, it would just be amazing. Just one day.”

Ben Lott via email 2018

The effects of his fall had been stealthy, shadowing Ben, then suddenly smothering him.

At first his words became slurred. Then he lost them completely.

He lost his job at a rural supplies company, he lost his partner, his savings, his self-worth.

In their place came an inability to balance and walk, migraines, and constant nausea.

Sometimes he couldn’t even remember his name, so he added notes to his phone’s alarm, so when he woke each morning, he could remind himself who he was, how old he was, and where he lived.

Shifting home to his parents’ farm near Fairlie, Ben shut himself in his bedroom, unable to cope with the light, sleep his sole escape.

When he did emerge, he couldn’t bear noise, even the most basic things like the sound of cutlery on plates.

All the chairs in the house had carpet put underneath them so they wouldn’t scrape on the floor.

“It was hell, as a parent, to watch it happening,” recalls his father, Bill.

His speech, as friend Lori Watson puts it, “was muffled, mumbled, slow, unrecognisable. When small children speak and only the parents can understand them – it was that, times 1000 more. We played a lot of charades.”

Previously a top equestrian, Ben found he couldn’t ride any more, and was forced to sell his precious horses.

Doctors struggled for a diagnosis, beyond the fact he’d suffered traumatic injuries to his brain and neck, leaving Ben enduring months of painful rehabilitation and repeated tests, with little progress.

At one point, those treating him said he should abandon any goals in his life.

At another, he was told he could perhaps hope to be a part-time forklift driver, a suggestion that reduced Ben to tears.

Feeling his recovery had stalled, and sensing officials were content to consign him to a life on drugs and benefits, a life dulled, and devoid of aspiration, Ben decided to quit ACC and go it alone.

“He was just determined to get better,” remembers his mother, Maureen. “He couldn’t live like he was.”

Instead, he gathered a group of friends and sports professionals around him, and pushed to get his life back.

Central amongst these people were Scott and Sue Worthington who’d kept in contact with Ben ever since that first garbled phone call.

“Ben’s a very authentic, driven person,” says Scott. “Extremely loyal, very determined, but most importantly, doesn’t really rely on anybody else to get things done.

“And when you’re in the state he was in, one of the most difficult things was for him to accept help.”

The first time they met after the phone conversation, Scott was shocked,

“What I saw was a broken Ben – in every respect.”

However, Scott could tell Ben thrived in the outdoors, so they began taking gentle trips into the mountains.

“And that wasn’t easy in the early days,” recalls Ben. “I couldn’t even get down hills without being on all fours.”

But every time they returned, Ben would be noticeably better.

Gradually, these “missions” progressed to the point where they would fly into parts of Fiordland whose contours hadn’t been crossed by anyone before, then make their way to the coast by foot and packraft.

As Ben later wrote: “I wouldnʼt be alive without these trips. Getting into these wild parts that are so remote gives something to look forward to … No chance to think about whatʼs been lost, just one foot in front of the other, finding a new normal.”

Scott railed against the idea Ben should have no goals, considering this tantamount to a slow death sentence for an obvious high achiever like Ben.

One day, Scott asked Ben what big goals he did have.

Ben demurred a bit, but then mentioned the world’s longest and toughest kayak/canoe race, the Yukon 1000, which travels 1000 miles (1600 km) down the Yukon River from Canada, above the Arctic Circle, and into Alaska’s heart.

Scott had never heard of it, but without thinking, said he’d do it with Ben.

From that point, their missions developed a twin focus: helping Ben’s rehabilitation, and training for the Yukon race, which became something of a holy grail.

But all the time, there was a parallel strand to Ben’s recovery.

Scott’s wife, Sue Worthington, had worked in advertising and copywriting for years, with her company Big On Writing dealing with everyone from big corporates to political parties.

In 2018 she saw a social media post from Ben with an audio of his pained attempts while learning to read again, overlaid with photos of his achievements before the accident.

In that 30-second clip, Sue realised Ben had captured how his life had been ruptured.

Spying a creative streak, she suggested he work with her on some advertising videos.

Before long, Ben had become her most trusted employee, finding new clients, rewriting companies’ websites, and driving the business.

But scepticism and prejudice dogged Ben from boardroom to boardroom, because of his speech.

“And I remember distinctly, we were in front of one client, and they literally ghosted him in the meeting, they didn’t talk to him, they didn’t do anything with him,” recalls Sue.

“And he walked away from that meeting, and he was really silent.

“About six months later, I said to him, ‘Your English has improved out of sight.’

“And he said, ‘I’ve been practising every day since that meeting.’ And that’s what Ben does.

“We don’t work with that client now.”

In May 2022, Ben became Big On Writing’s managing director and half-owner of the company, which now has clients and staff across the world.

“I guess my philosophy in life is that you never judge a book by its cover,” says Sue. “And that’s probably why I took Ben on board.

“But what I discovered through this process is that a book is always judged by its cover. And what Ben had to do was make sure that cover was really, really good.”

“Send not your foolish and feeble, Send me your strong and your sane.”

Robert Service, The Law of the Yukon

The idea of taking someone in Ben’s condition to compete in one of the world’s toughest endurance events, seemed far-fetched and likely doomed to many, including some of Ben’s medical specialists.

But Scott refused to consider anything other than making the start line and then paddling for however long it took them to finish.

Covid, in a strange way, helped, delaying the Yukon race for two years.

In that time, Ben became stronger, his speech recovered until it was hard to detect defects, and outwardly he seemed to be almost back to where he was before March 2018.

But the migraines, the interminable tiredness, the recurrent nausea and vomiting, the light sensitivity, all remained, by now a wretched rhythm he’d learnt to march with each day.

“99% of people wouldn’t have had the recovery Ben had,” says Sue.

“Actually, it’s nothing short of a miracle. But it wasn’t a miracle – it was just hard work. He just pushed through pain, he pushed through people trying to say no.

“I’ve got to be honest, if it was me, I would have topped myself. He never had a good day, but he always believed the next day would be better. And that taught me so much.”

Ben was happiest in the hills and on the water as he and Scott trained for the Yukon, his stride and stroke improving, helped by friends like three-time Coast to Coast champion Simone Maier, and kayak coach, Olympic silver medallist, Ben Fouhy.

But just as Ben was regaining his endurance, crisis hit Scott.

In January 2022, less than six months from the race, Scott collapsed and had to be flown to Dunedin Hospital for back surgery, crippling his training for weeks.

Compounding this was the discovery of a melanoma on his back, which had to be cut out, leaving him with intersecting surgical scars.

But he never considered pulling out, living by the mantra a friend once shared with him: “It’s only pain – it goes away.”

However, it wasn’t only pain, with tests showing the melanoma had likely spread into other areas of his body.

“Do I expect it to have gone further? Probably,” Scott said, standing beside a Fiordland river the pair had just packrafted down during training.

“You know, you’ve got to die of something. To be quite frank, it’s the furthest thing from my mind.

“When your time’s up, your time’s up, and we’re having a hell of a lot of fun.

“And, you know, for me to actually not deliver on my promise to Ben was just never gonna happen.”

A few days before they flew to the race start in Canada, the pair stood in Scott’s garage near Tarras, swaddled in puffer jackets, surrounded by gear, ticking off checklists.

There was everything from satellite trackers to swim goggles, medical kits to map books. Carabiners, survival blankets, water filters, strobe lights, a mountain of dehydrated meals, a million other things.

Ben realised how far he’d come, and knew how much getting to the Yukon would prove.

But looking back was also hard.

“Because there’s parts that I’d dearly love to have hung on to and kept. But you’ve just got to let it go.”

You can read Part Two of Finding Ben here.