Originally published on stuff.co.nz, by Mike White & Iain McGregor, January 6th 2023.

This is Part Two of Finding Ben, the story of Ben Lott’s remarkable recovery from an accident that almost ended his life. You can read Part One here.

The video above tells Ben’s full story.

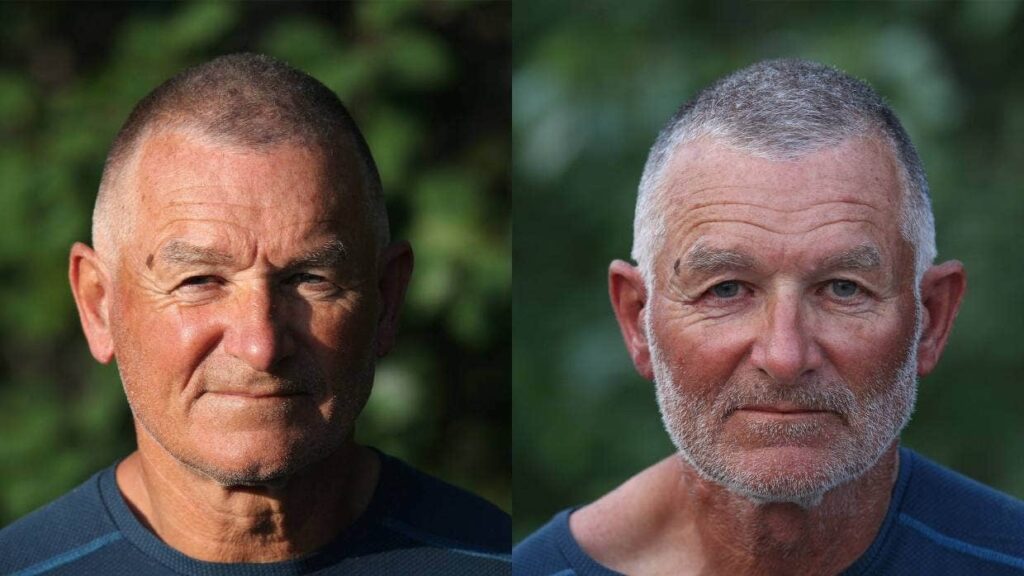

In March 2018, Ben Lott fell and suffered a severe brain injury while competing in an adventure race. Two days later, he was found disoriented in the middle of a forest by fellow racer Scott Worthington. Over the following days, Worthington helped Lott make it to the race finish. Over the next four years, he stayed beside Lott while he made an incredible recovery. This is the story of Finding Ben.

“I ask (potential entrants), ‘But do you know how to cope with the big empty? Because there is a whole lot of it up here”

Peter Coates, Founder of the Yukon 1000 race

In a world full of extraordinary athletic challenges and exceptional physical feats, the Yukon 1000 remains unique.

Beginning in 2009, it attracts a mix of dreamers and the planet’s best adventurers.

In 2022, nearly 3000 teams applied for the 40 starting spots.

Race director Jon Frith describes it as the world’s toughest endurance and survival event.

“It’s at the high end of risk – maybe a little over.”

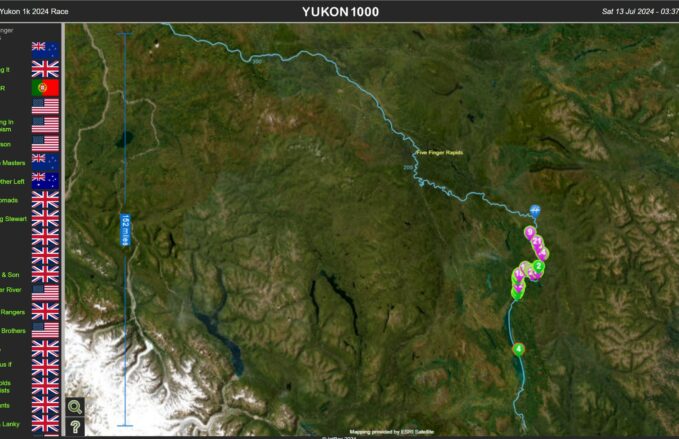

Crews begin in Whitehorse, in Canada’s remote Yukon Territory, and in either kayaks, canoes or on stand-up paddleboards, follow the route of the 1896 Klondike goldrush north towards Dawson City.

Then they bend west, across the border into America, and track beyond the Arctic Circle to the finish at the Dalton Highway Bridge in the middle of Alaska.

Each day they paddle for 18 hours, and must then take a six-hour break in which they have to cook, set up tents, snatch a few hours’ sleep, filter drinking water, break camp and push off into the flow again.

They must be totally unsupported, and have 10 days to finish.

Amongst 2022’s competitors were polar explorers, those who had rowed across oceans, another who had climbed Mt Everest.

Despite Ben being laid low by Covid as soon as he arrived in Whitehorse, and Scott needing a tooth pulled on the race’s eve, the pair remained unfazed by their competition, confident in their years of preparation and shared adventures.

On Saturday July 2, Ben, 32, and Scott, 64, escaped Whitehorse’s summer-baked streets and entered the air-conditioned respite of a conference room where Frith stood preparing to give the final race briefing.

With a bluntness born from a life in the military, Frith warned of forest fires, bears, moose, rapids, high water, and the need to be utterly self-sufficient, as rescue simply wasn’t possible in most locations during the race.

“When you’re out there, you’re out there … There’s no Googling your way out of this shit.

“It’s a really special place, so cherish every moment. It’s a race, but it’s one hell of a place.”

“Let me be clear – unless you are a masochist on a rapid weight-loss plan, I don’t suggest you do the race”

Dan Achber, former Yukon 1000 competitor (who lost 9kg during the race).

Shortly after six o’clock the next morning, Ben closed his hotel room, stepped into the sun, and set off along Whitehorse’s waterfront to the race start.

An hour earlier he’d convinced himself he didn’t want to do the race

“Coz why the hell would anyone enjoy this?”

But the excitement had quickly returned, together with some perspective.

“It’s kind of like the end of a four-year grunt that everyone said wasn’t possible and I’d never be able to do. The moment we sit in the boat, it’s a bit of a, ‘I did it’”.

As Ben and Scott stowed provisions for 10 days, slathered on sunscreen and anti-chafing cream, and wished fellow competitors good luck, there was a sense they’d already completed the biggest challenge.

“It’s the end of four years of absolute hell, really,” said Ben, his voice cracking. “But hey, we did it, we got here to the start. And that’s all that matters.”

Scott, too, choked back tears as he thought about everything they’d gone through together to get here.

“It feels awesome. Three years, and to be here is just the best. So we’re gonna give it our best, and enjoy the adventure. Yep, be a few tears at the end, unfortunately.”

At 7.30am, Frith shouted “Go”, crews raced to their boats Le Mans-style, and they paddled quickly into the Yukon’s current, the cries of well-wishers chasing them downstream.

Huge winter snow dumps in the mountains had begun to melt, meaning the river was high and fast. While that helped competitors’ progress, it meant most campsites were flooded, and just getting to shore required dangerous manoeuvring.

And when they did manage to stop, the area had to be scouted for bear prints. If bears or moose were nearby, they had to keep paddling for several more kilometres before again trying to land.

Ben and Scott had spent so much time together, they immediately slipped into a routine, with meals eaten on board, and about four hours’ sleep grabbed each night.

The mosquitoes were murderous, the campsites waterlogged and sloping, the temperature tipping into the 30s.

Forest fires, which had cut the only road north through the Yukon territory, blocked the sun and spread along the river’s surface.

Rapids and whirlpools capsized several boats, one crew carried downstream for 20 minutes before making it to shore, then spending several hours in their sleeping bags to combat creeping hypothermia.

Thunderstorms with lightning swept over the crews, forcing them to seek shelter.

By Dawson City, the race’s halfway point, three crews had pulled out.

But Ben and Scott steered away from calamity, navigated their way through sections where the river stretched 4km bank to bank, and simply kept on paddling, 18 hours day after day.

Ben developed trench foot from the constant damp, backs were rubbed raw, and Scott’s fingers locked at painful angles from the repetition of gripping his paddle.

But that’s alright, Scott would remind himself. It’s just pain – it goes away.

On the evening of Saturday July 9, after six days, and 15 hours, the pair paddled under the Dalton Highway Bridge, 800 km north of Anchorage and the only crossing point of the Yukon River in Alaska, and nosed into shore where Frith and supporters waited for them.

They were eighth of the 21 teams to complete the race.

There was champagne, there were hugs. There was a sense they could have carried on further, rounded more riverbends, even reached the ocean another 1000 miles away.

But above all, there was the feeling they’d somehow pulled off something that seemed an utter pipe dream three years before, when Ben was incomprehensible and all but crippled.

Relief and realisation all wrapped in a swirl of backslapping.

They carted their bottles of bubbly to the nearby truckstop – an iconic diner that features on TV series Ice Road Truckers – and buried themselves in burgers and chips, a hundred vignettes and race memories rapidly traded with other finishers gathered there.

Then they once more pitched their tent, at the back of the truckstop, beside two giant rubbish incinerators, and with crows watching on, and the midnight sun still orange above the horizon, crawled inside.

“Now this is the Law of the Jungle – as old and as true as the sky,

And the Wolf that shall keep it may prosper, but the Wolf that shall break it must die.

As the creeper that girdles the tree-trunk, the Law runneth forward and back,

For the strength of the Pack is the Wolf, and the strength of the Wolf is the Pack” – Rudyard Kipling, The Law of the Jungle. Written on the dry bag of a Yukon 1000 competitor.

Ever since the accident, ever since his life began falling apart, there had been inevitable temptation for Ben to focus on what he’d lost.

And he succumbed often in the early days, the hole in his life easy to tumble into, the way out hard to see.

His speech, his movement, his friends, his partner, his job, his horses and riding.

His self-esteem, and the many dreams every young person has, all stolen in an instant.

It would have been the simplest route to accept the fatalism of health officials, and the boxes bureaucrats wanted to place him in.

But there was always a “f..k that” attitude with Ben. “F..k them.”

This was the kid who didn’t want to play rugby in the Southland village he grew up in.

Instead, he played netball.

“Ben was always a tough kid,” remembers his mother, Maureen Lott. “‘I don’t care what people think of me.’

“He just did it. And down there, playing netball as a boy wasn’t the done thing.”

After the accident, Ben knew he just had to listen to what his body was telling him, where it hurt most, and get help with that.

In time, he accepted life would never be the same again – but he was still Ben.

And he figured if he worked hard enough, then surely improvement would come.

He did his part, and was encircled by others who helped him: the friends in Canada who flew him first class to Vancouver for Christmas for respite; the friends in Wānaka, where he now lives, who kayaked and mountain-biked with him; the friends who took him to the top of the mountain and pushed him off so he could learn to ski again.

What began near Fiordland’s Wairaurahiri River with his fall, and ended beside the Yukon River in Alaska, couldn’t have been predicted – but what happened was something Ben realised he simply had to get beyond.

And somewhere between those two rivers, he found a way.

But for Ben, this story was never going to finish on the banks of the Yukon.

This was just a first step, a launching point for more adventure.

Already he’s mapped out several years of major missions, threaded through a manic business life.

Life is full, and good once more.

For Scott, there’s extraordinary pleasure in witnessing Ben’s recovery, and huge enjoyment in having spent so much time with him.

“I mean, you can give cheques to Save the Children Fund and all those sort of things, which are great. But there’s something really nice about helping somebody in your community that needs help.”

Sue Worthington says many people believe their whole world has fallen apart at some stage.

“And I go, yeah, but you just wait three or four years, because I’ve seen phenomenal changes in Ben, and I’ve seen it in other people.

“So just hold on.”

Hold on, and move on, says Ben, who has learnt not to second-guess the future.

“It is what it is. If it gets better, it gets better but don’t think about it. Just got to keep going and keep trucking.

“I’ve got this far, if I can get this far now, I can only go two or three times further down the road.”